This blog is now an anime blog, but only by technicality and only for a minute. As soon as I write my next post about whatever, it will only be half an anime blog, and the fraction will continue to decrease from there…unless the second post happens to be about anime as well, in which case I’ll hang myself as a matter of principle and public service.

Seriously though, this is just my blog to practice writing; it’s something I love to do, so I’ll just go with what inspires me, and what happened to inspire me this time was my affection for one Tomoko Kuroki. If you hear a distant shrill that sounds something like “REEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE,” it’s probably because I keep putting the surname second. I’m likely considered a casual anime fan by most standards, but when I find a show I like, I watch the fuck out of it – I’ve burned through Watamote around fifteen times now, and I show no signs of slowing down. All of my friends love Tomoko as well, one of them going so far as to legitimately waifu her. I’ll tell you more about him later. We talk about her pretty regularly amongst ourselves, and our sentiments usually jive unless we venture into fetish territory. However, when I go out on the internet, I see different opinions, and – like any well-adjusted adult – when I encounter someone with a different opinion I call them a faggot and then write a blog post.

At least once a week, I see a thread that wonders something to the effect of “how can anyone like this character?” and then goes on to assert that she’s a shitty person who has no redeeming qualities whatsoever (the first part of which can absolutely be true depending on what definitions you’re using, but I’ll come back to that later). A lot of the defenders’ arguments can be summed up as “because waifu.” That or they attempt to scrape together a few examples of Tomoko being decent, which is pretty hard to do. I’ve also seen people argue that she’s just sort of too pitiful to hold to normal standards…which is also kinda true. Mostly, though, they just point out that she’s as pathetic as us, so that’s why we like her.

Then we have Digibro (n-not that I like him or anything), who actually gives us a logically-constructed answer to this question, and it’s pretty neat in a lot of ways. However, that answer implies something about Kuroki which is (to me) much worse than any of those OPs who call her a shitty person ever said – that she’s not a person at all. I’ve watched this dude’s video [link] a few times now, and the thesis I took away from it goes something like this: Tomoko is antisocial and neurotic in more or less every way a person can be short of the ones that land you in jail, and when coupled with how consistently she seems to get fucked by life, we’re left with someone who is such a disaster that she couldn’t possibly exist. With that in mind, she is better parsed not as a character, but as the embodiment of an idea – a sweaty-palmed, spastic monument to “what people are like at their worst and most self-destructive.” She’s too exaggerated for anyone to identify with comprehensively as an individual, but most people are going to relate very, painfully closely to certain parts of her experience, and our affections for her are going to arise from those very specific congruencies. We feel relief that someone else can be that stupid and/or unfortunate, and it makes us feel better about ourselves. Essentially, liking Tomoko despite her flaws means liking ourselves despite our flaws. Digibro does a good job of explaining why someone (or a lot of people) might like Tomoko, but at the expense of her very humanity.

Before I go any further, I’ll back to that last bit and jump on the words that probably set off your spaghetti alarm (assuming its threshold is high enough that it didn’t begin an emergency abort sequence after the first paragraph): “at the expense of her very humanity.” Right about now, you may be tempted to point out that she’s a cartoon character, that therefore she has no humanity, and then gently pat me on the shoulder and suggest that I take my medication. Well guess what? I already took it. All of it. For realzies though, I’m making a genuine attempt here at an intellectual (lol) discussion. Treating a cartoon character as though she’s an actual person is its own philosophical clusterfuck that I could write a whole other thing on, but that’s not what I want to talk about right now, so just indulge me.

This brings me to a big piece of context: I don’t consume media with a critical mindset. I don’t normally think about themes or symbolism or any of that stuff, and maybe these ramblings are just an effort to drag the conversation back down to my level – a purely emotional one. I enjoy things by becoming immersed in them rather than analyzing them, to the point where it’s less like enjoying a work of fiction and more like catching a glimpse of an alternate reality. I take any parameters the fictional world presents to me at face value and as gospel for the duration of my stay there, and if any of them are subsequently violated, my attempts at explanation are constructed in-universe instead of metatextually. So like, if someone’s acting “out of character,” my first inclination is to wonder what information about their emotional state I’m missing rather than to call it “bad writing.” I guess what I’m saying is that I’m more interested in the psychology of the characters than that of the writers.

Now, I am by no means saying that I just like anything and everything and don’t question it; I am probably one of the pickiest motherfuckers in the world when it comes to media, and you can ask any of those friends I mentioned earlier just how impossible it is to get me to try something new, and how improbable it is that I’ll actually like it. What I am saying is that when I do like something, I get sucked into it so deeply that the idea of defending a cartoon character’s “humanity” doesn’t seem weird to me until I have to stop and think about it. If nothing else, maybe I can provide you with a different lens through which to go back and re-experience your favorite stories. I’ll return to this later, because it raises an interesting question, and not the one you’re thinking of.

Moving on…

Tomoko Kuroki could be a symbolic representation of self-destruction. I won’t debate the validity of this interpretation because there’s no way to, and I think it’s cool. To me, however, she is something subtly but importantly different – a person whose life is completely out of control. I’m going to bring back what struck me as one of the key points in Digibro’s post, in his own words: “No one can probably relate to every single scenario that Tomoko finds herself in, but most have probably lived a few of them so specifically that it hurts to see them animated.” I think it’s pretty reasonable to assume that this is going to be true for most people, and it’s fairly true for me. I definitely can’t draw a precise personal parallel to every horrible thing this poor girl does or is subjected to, but there are a few scenes here and there where I cringe and go “oh yeah, I did that.” Still, those moments are few and far between. Most of Tomoko’s misadventures involve her crippling social anxiety, which is a problem I just don’t have. Everyone is self-conscious to varying degrees and I’m no exception, but I’ve never had to deal with anything approaching that level of awkwardness. I don’t like Tomoko because I can relate to all of her experiences or even because of the few to which I can, and while I’ve got no shortage of psychological problems, It’s not even because of her obvious mental illness. Rather, I can very much relate to the core of the problem: her frame of mind.

Like I said a minute ago, Tomoko is a person whose life is completely out of control, and I mean that in a very specific way. It’s not that her life is outside her ability to control, it’s just that her mindset makes it seem that way from her own perspective. If you wanted to psychology this shit, you could say that she is devoid of self-efficacy – one’s belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task . On the surface, this might sound wrong; whenever Tomoko comes up with a new get-popular-quick scheme, she seems very confident that it will work. Yet every effort to improve her situation is – in her own eyes – thwarted by fate. Take for instance when she tries to start a club at her school to create a setting in which she can finally make some friends, only to have the application rejected. Or when she tries to start a livestream in hopes of becoming popular on the internet, but just ends up getting jeered by the viewers until she bails. Or how about the time she tried to get a job working at a trendy cake shop only to get stuck working at a cake factory? Sounds like misfortune after misfortune, right? This perception that she’s unable to change her life only sets in after the fact, and that’s where the other half of the equation comes in: a lack of self-awareness.

While Tomoko is incredibly self-conscious, she has almost nothing in the way of self-awareness – she’s very concerned that people will judge her, but never stops to actually judge herself. True, she has moments of clarity where she’s like “yeah, I suck,” but on the overwhelming whole, she refuses to acknowledge that the plethora of things that are wrong with her life are in any way her fault. You might think this would just be part of having no self-efficacy, but that isn’t true; there are people with poor self-efficacy who – despite feeling on an emotional level that they can’t fix their problems – still understand intellectually that it’s a psychological hangup they’re dealing with. They understand that they have a problem, and (theoretically) can at least ask for help. If that sounds unlikely, let me tell you about my friend, who just happens to be that same one I mentioned earlier who waifus the very subject of this discussion. Pretty much all he does is sit in front of his computer and jack off…in fact that’s all he’s done in the entire time I’ve known him. Whenever we tell him to get a fucking job, he explains that he’s too much of a lazy piece of shit to do so, and is content to live in poverty and squalor rather than put in the effort to get his shit together. He actually got a job once, but quit after like a week and went back to jacking off in the middle of a room which he freely admits has become “its own ecosystem.” He feels like he doesn’t have what it takes to change his situation – meaning he lacks self-efficacy – but intellectually he understands that it’s his own stupid fault because he’s a lazy piece of shit and goddamnit Dan just take a fucking shower and clean up your room jesus christ you fucking stoner.

Anyway, my friend at least has self-awareness, which is something Kuroki lacks. She doesn’t understand that all those ideas I mentioned a second ago failed because of her. The club application was rejected because she didn’t even come up with an actual idea for a club. The stream was lame because she made no attempt to plan it beforehand. She ended up on a cake assembly-line rather than a cool cake café because she didn’t bother to ask her mom a single question about what the “friend who made cakes” actually did. All of these outcomes that seem on the surface like “bad luck” or whatever only came about due to a monumental lack of effort and consideration on Tomoko’s part. Now you can start to see what I mean when I say that her life is “out of control;” it’s a circular relationship between having no self-efficacy and having no self-awareness – she feels like no matter what she does, nothing ever changes, when in reality nothing ever changes because she makes no thorough, intelligent effort to do anything.

Don’t get me wrong, she makes a lot of efforts, but they’re always acts of passion or desperation. Tomoko never takes a discerning approach to solving any of her problems, because she doesn’t seem to think she has any; everyone else does, or at least she tells herself that. She’s not a quiet girl, she’s actually charming and outgoing, but people keep putting her on the spot and she can’t think of anything to say. She doesn’t hang out with any of the girls at her school because they’re all dumb sluts. Guys just don’t appreciate girls like her because they’re all chasing those aforementioned sluts. It’s in the title of the show for fuck’s sake: No Matter How I Look at It, It’s You Guys’ Fault I’m Not Popular! Now, I could go off on a tangent about how awkwardly-worded that is, and how I sometimes drag my nails down my face while thinking that there must – there must – have been a better way to translate it into English…but I won’t (I’ve also seen It’s Not My Fault That I’m Not Popular, but that doesn’t quite communicate the same level of blame to me). The point is that Tomoko has her head so far up her own ass that she’s become trapped in a self-perpetuating delusion of helplessness.

…

What about No matter How I Look at It, It’s Y’all Niggaz’ Fault I’m Not Popular? Like, all joking and questions of propriety aside, doesn’t that flow better?

Before anyone says I’m ignoring it, I want to point out that there is a third part to the equation which I mentioned a couple times earlier: Tomoko obviously has a debilitating anxiety disorder. Somewhere in my first run-through of this show, I stopped and wondered just why the hell no one has actively tried to help her with it yet. Why hasn’t her mother or another adult – a teacher, maybe? – stepped in and been like “maybe you need professional help.” Then I realized that nobody really knows. Tomoko obviously has no problem interacting with her family (at least in terms of anxiety), so it’s likely that they rarely see it, and her lack of friends – which her mother probably attributes to laziness and a love of video games/the internet – means there aren’t any other parents she interacts with who might notice either. Almost all of the drama she goes through at school takes place inside her head, and if you don’t believe me, take a moment to imagine what Watamote would be like if we weren’t privy to Tomoko’s thoughts. To the average adult she would just be “that quiet girl,” assuming they even noticed her in the first place, which they often don’t seem to.

The actual question I wanted to address here though is whether or not Kuroki’s social anxiety is the root cause of all her problems. It’s undeniably a massive contributing factor, but is it the entire reason behind her negative mental feedback loop or not? I would argue that it’s definitely not. Why? Because, to be quite frank about it, having social anxiety doesn’t automatically make someone a delusional asshole.

On that note, let me return to something that I said I would: the idea that our little spaghetti princess could be called a shitty person depending on what standards you’re going by. You might think I’m about to write some abstruse deconstruction of what good and bad people are, and end it by telling you that in my eyes and by my own criteria, she’s actually good person.

I’m going to, but not yet.

Tomoko is selfish, narcissistic, and indifferent to the feelings of others. She treats people however she wants without even the slightest inkling that she should feel remorse. The only time she attempts to “atone” for her actions is when it serves her interest, for example when she replaces the drink she stole from her brother – something she obviously should’ve done anyway – in an attempt to persuade him to go to that photo booth with her. She has no discipline and no real goals in life. Her attempts at “self-improvement” are frequently retarded on an almost objective level and undeniably shallow, and every time I start to feel bad for her, the next words out of her mouth usually stomp that burgeoning sympathy into the dirt.

In episode twelve, for example, she begins secretly recording her classmates’ conversations so that she can figure out what they think of her. When I first heard this plan, my heart started to break – it seems like a desperate attempt to hear someone say just one nice thing about her. Then she reveals that her intent is to use whatever they say to fine-tune her persona and manipulate them into liking her and doing whatever she wants, which made me roll my eyes, shake my head, and just move on. Yes, it’s even more pathetic and desperate than I originally thought, but the derisive glee with which she outlines her plan just makes me want to legally adopt her so I can slap her without any criminal ramifications (that’s how kids work, right?). Once again, she only cares about other people and their opinions insofar as they serve her own ends, not on any empathetic level. When she discovers that nobody is saying anything about her at all, the only thing I could think was “yeah, serves you right.”

Or how about episode eight, with her cousin Kii? Do I even need to say anything else? Do I need to say anything else at all? The entire thing is so disgusting it makes me want to meme.

So why do I like Miss Kuroki so m- ?

REEEEEEEEEEEE-

So why do I like Kuroki-san so much, and if I do, why am I so hard on her? Why has this big dumb essay whose initial intent seemed to be the defense of her nonexistent, cartoon-character humanity seemingly (d)evolved into a detailed explanation of why she sucks?

I don’t think of Tomoko as a symbol, but if I had to, I suppose she’d be the patron saint of those who are completely lost, because that’s what her life amounts to if you ditch the psychoanalysis crap and look at it in more practical terms. The only “goal” she has – becoming popular – is superficial and probably unhealthy, and she has no clue how to achieve it. She can’t treat people decently, let alone make meaningful connections with them. She has no confidence and can’t criticize herself, and therefore everything seems to happen to her rather than because of her. She says something to that effect at one point – “why does everything always happen to me?” That line is funny because of the very thing I’m talking about; we can see that most of her woes are of her own making, but she can’t. Anyway, I can list all her problems over and over, but to sum it up as a single concept, she is utterly lost, and one of the biggest reasons I love her is because I’ve been there, and I’ve been there hard. I won’t go into detail about my specific set of circumstances because they’re irrelevant. I can’t understand the experience of being a teenage girl with social anxiety, but I can understand the feeling of looking at one’s life, seeing nothing good, and coming to the conclusion that the world is trying to screw me and everyone is a fucking dick.

I can’t think of Tomoko as a symbol because I’ve shared with her one of the most meaningful things two people can share: a state of mind. I can’t afford to think of her as someone too broken to exist, because however unlikely it may seem, those people are out there and I know this to be an absolute fact. I love her despite all her flaws not because I want to love myself, but because the fact that people were willing to do the same for me is the only reason I’m alive right now and typing this drivel. Once in a while, I find these people in real life, though they’re few and far between. I do what I can for them, but often there’s not much you can do. When someone is so far gone that even well-intentioned people seem like enemies or go unacknowledged, really the only helpful thing you can do is just keep them from inflicting any lasting damage until they find a way out by themselves, and that can take a solid minute. You can care for them and that’s about it. Oh yeah, but you can’t let them ruin your life, that’s a big no-no, so sometimes you have to be hard on them. You have to be willing to call them out when their bullshit becomes egregious, and even keep them at an emotional distance if necessary. Self-pity does not benefit from more pity. And hey, sometimes, if you tell someone they have a problem over and over and over again, it slips through the seemingly impenetrable denseness. Despite how reprehensible Kuroki can be and how hopeless and incurable she seems at times, she has a strong desire for a human connection and she never stops trying.

That’s another big reason that I’m always cheering this girl on despite her being a massive pain in the ass: she never gives up. No matter how misguided her plans are or how utterly they fail, she’s always got another one, and however pointless the notion of “being popular” is, buried somewhere within it is a simple desire for meaningful relationships. I guess this is the part where I get picky about definitions of good and bad people. She’s definitely not a stellar individual in her current state, but I believe this drive she has is fundamentally good and makes her worth salvaging. Imagine what an older, more self-critical Tomoko could accomplish if her anxiety was under control and she learned some empathy; that determination and resilience could be a powerful thing if applied correctly. I think what I’m saying is that while you can’t call her a good person in her current state, neither can you call her a bad one, and more importantly – with the proper guidance and patience – she could be a great one.

You can probably tell I’m basing all of this off the show and that I haven’t read the mango, but there are two good reasons for that: (I believe) Digibro’s article/video did the same, and I can’t read. Okay, so there are zero good reasons, but there’s one after-the-fact justification and one awful joke. Honestly, I just don’t read mangoes, but the moment I finish writing this crap, I’m going to make Watamote my first for two actually good reasons: number one, I’ve watched the anime so many times that I have it memorized and I desperately need more to work with, and secondly – from what I’ve heard, anyway – Tomoko starts to get a little bit better in the parts beyond what the animation covers, and I want to examine that part of the arc to see how she matures. I mean, even at the end of the anime, she starts to have fleeting moments where reality seeps in. I’m thinking in particular of episode eleven, when she daydreams about what the cultural festival would be like if she were in the music club. She begins with her usual “I’m popular and awesome (and so cute in that rrrrrocker girl outfit)” fantasy, but then quickly reexamines her expectations and we get her standing outside a door listening to the other club members talk about how weird she is. Obviously pessimism is just as bad as delusional optimism, but those little pinpricks of doubt are the seeds of self-awareness.

I crawled up my own ass again for a sec, but another reason I bring up the guava is because thinking about this stuff got me curious about authorial intent. Was Miss Kuroki (fuck off) intended to represent an idea or a person? Was she constructed from a more intellectual standpoint, or a more emotional one? Maybe right in the middle? Of course I wanted to know if I hit close to the mark, but I was also curious about the people behind this character I like so much. I will say that I got more of an answer than I expected.

The creators of the original passion fruit go by the pen name Nico Tanigawa. I don’t know if that’s one of their names, an amalgam of both, or neither, and it seems like nobody else does either. The writer is a man and the artist is a woman, that much is known, though it seems not by many. There’s a pretty common perception going around that Nico Tanigawa is a single individual and a woman, but all my research (i.e. stoned googling) indicates that we’re dealing with a duo, and the writer is a dude. For all I know, maybe remaining mysterious is common of banana artists, but goddamned if these two aren’t incognito as fuck. I couldn’t find a single picture that anyone even claimed was of the authors. I found two interviews, and while one could barely be called such they still bore some fruit, so to speak (do you see what I’m doing here?). The original pages for both were dead; all I got were archived copies. Still, in what little I was able to pull together, I got quite a dose of emotion.

First, read [this].

Yeah, it’s a translation – and a wonky one at that – sitting on an anonymous pastebin, so I can’t prove it’s legit, but [here] is the reddit (I know) post that led me to it. The short discussion explains the deal: the interview was posted on the Japanese fansite linked in the reddit post, someone translated it, the pages were removed because copyright…? and someone cuntpasted it (please tell me somebody else remembers that term) to the bin I linked earlier. My internet sense tells me this is legit, and I’ve treated it as such.

Also, have a look at [this]. It’s a short Q&A originally posted on Gangan Online (if you want a more complete picture of what’s going on with that, read [this]), of which we can only see a reproduction. It provides no new information, but it does provide another small look at the creators’ personalities that appears very consistent with what the other interview showed. Also, both interviews manage to reference another interesting and probably obvious fact.

Anyone who goes to the secret, spooky land of 4chan knows that Tomoko is hugely popular there, which I guess is ironic in and of itself, regardless of the site. Then again, if there was one place where she was going to be adored and accepted, I can’t think of a more likely one. Yes, there are plenty of people who post “how can you like her” threads as I mentioned all the way back at the top, but despite a few incorrect opinions, she’s embraced there to the point of memetic status. To give one of my favorite (and objectively one of the worst) examples:

Everyone – I don’t care what board you’re from – has both an understanding and a preconception of what a post is going to be like when they see Tomoko. My own involvement with 4chan dates back to early 2009, (and for anyone who recognizes the significance of that time period, the answer is yes, that’s exactly how it happened, and I know I’m the worst). However, at the time of Watamote’s – and more importantly Tomoko’s – adoption by the site (primarily /a/ and /v/ from what I can gather) a few years later, I wasn’t an anime fan so I did not witness the spectacle firsthand. Still, even sitting on the periphery, I saw a girl who is hopelessly unpopular in her own world elevated to ubiquity in this one.

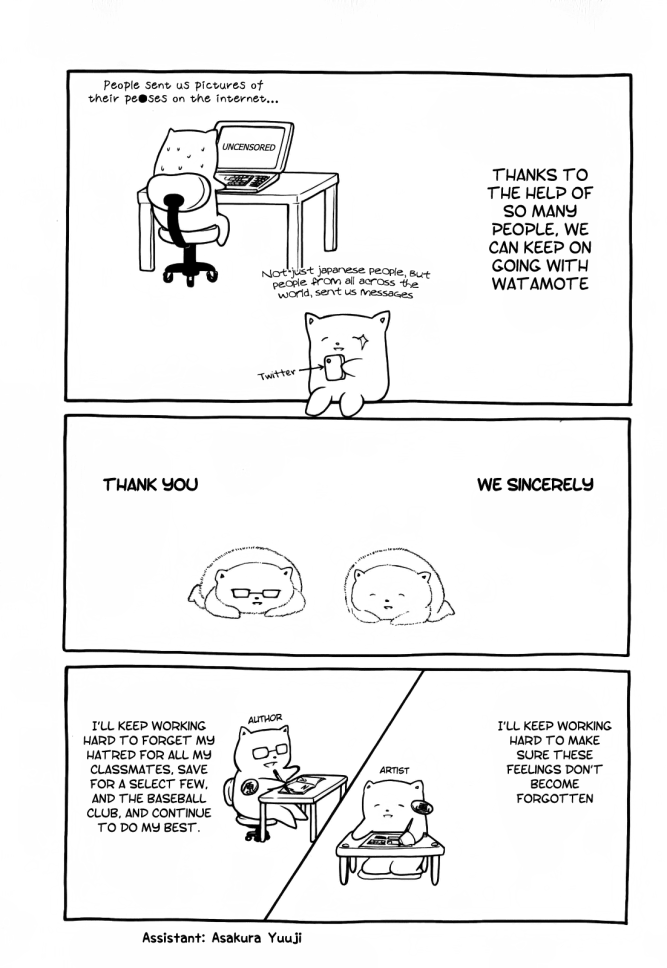

Anyway, the long and short of it is that the attention given to the manga by 4chan plastered her across the internet and resulted in a fuckton of sales, to the point where it got the creators’ attention. From what I understand, they didn’t expect to be able to continue the series for very long, but this outpouring of interest enabled them to. Among other gestures, they made a short comic in thanks to their unexpected fanbase:

Oh yeah, some people also sent pictures of their dicks. /a/ blames it all on /v/, but it looks like the creators were completely chill about it. They even advertised 4chan’s love of their work on a volume of the mango [see article here]. If you’re brave enough to dig through archives, you can find more entertaining tidbits, but I’m getting sidetracked.

That part’s all good fun, but what really interests me are the personas of the creators that these interviews and events project. When it comes to direct interaction with others, the author and the artist are good-natured and obviously have a sense of humor. It’s pretty apparent how grateful they are to their fans, and that they love what they do. Everything else they say, though, conveys a very different set of emotions. Both of them – especially the writer – explain how isolated they were in their youth, and express a strong desire to keep their character that way:

The writer: When we had not decided the direction of this manga, I tried to make a new character who approaches to Tomoko. But it did not go well and I quit. Watamote is the manga that its story completes by Tomoko alone.

Interviewer: As the artist, do you want to make a new character?

The artist: Unless the writer’s ideas are exhausted, I want to make Tomoko fight alone. I think it is OK that only readers care for her.

Interviewer: In the end… Will Tomoko be happy?

The writer and the artist: (smile)

That is metal as fuck.

Also, we all know Tomoko as a slightly-sickly but adorable little anime girl, but she wasn’t always that way. The artist wanted to make her ugly, describing her original appearance as tall, gangly, and flat-chested (isn’t she already?) with tiny irises. She only made the character design cuter at the insistence of their editor, leaving the dark circles under the eyes as a sort of visual signature of the original idea.

At one point, the interviewer straight up asks the author if Watamote is based on his life, to which he replies:

The writer: Better say, “I give vent to my various feelings in my heart”. I am a very envious person.

But if you look at the last panel of that comic I posted up there, it seems like there are at least a few very direct correlations:

I’ll keep working hard to forget my hatred for all my classmates, save for a select few, and the baseball club

I’m not going to recount and scrutinize everything they said. You should read for yourself and draw your own conclusions. Whatever those may be, I think it’s safe to say that a lot of personal experience and a lot of emotion was put into Tomoko as a character. Like the writer said, he uses her to vent. I don’t want to say too much more, because picking this stuff apart feels like judging these people, and at the end of the day I know fuck all about them and their lives. What I will say is that I’m a douchey, wannabe Internet Tough Guy. I use a lot of bad words and (try to) make sarcastic jokes, but let me assure you that it’s all a façade and state this plainly for the record: I’m a little bitch, and I had tears in my eyes by the time I finished looking through all of this stuff. Call me a fucking faggot because I am, and I really can’t help it. To me, it seems Tomoko was made from a place of hurt, and the echo of that emotion made it through some bad translations and the ethereal faerie dust of the internet and kicked my heart in the ass. At the same time, it’s clear that the creators both enjoy and derive some measure of solace from their art, and that they appreciate those who love it. Realizing that made me feel just as much in the other direction.

As to my actual question about authorial intent, who the fuck really knows? When I read through this small amount of material, it seems to confirm my perspective, but I’ll bet that’s true for anyone. It’s a combination of confirmation bias and not enough information. The authors stay well-hidden and don’t appear to want much personal involvement in the popularity their work has achieved. Instead, they’re content to just present it, and maybe that says everything about intent that we need to know. As the artist put it: “Various readers read this manga various way. So, laughing or hurt, they feel various feelings. That’s it.”

They really do know their fans, though…

There’s one more thought I wanted to explore before I fuck off – a question I mentioned earlier when I was explaining my enjoyment of media through immersion rather than analysis: can a person such as myself even enter a discussion that attempts to examine a piece of art like Watamote from a metatextual perspective? Like, can I have a meaningful dialogue with someone like Digibro? Are we even talking about the same thing? Yes, Yes, and sort of. At least those are my answers, your mileage may vary.

(Just to drop the final layer of pretense, I’m actually a big fan of Digi and I follow him pretty closely. I do hope he reads this – and dude, if you are reading this, I hope it was at least interesting. I took your idea, screamed #YOLO and ran in the exact opposite fucking direction. What can I say?)

I mentioned earlier that I’m not trying to debate the validity of Digi’s interpretation or anyone else’s. In the end, I think my viewpoint serves better as a companion piece to more intellectual, “meta” deconstructions than as an argument against them. Tomoko Kuroki can definitely serve as the embodiment of all the worst things a person can be – according to the author, that’s what he intended her to be in some capacity: a way to vent his negative feelings and put them somewhere. But the idea that she’s not a character because nobody like her could exist is where my perspective fits in. She has a very human psychology to her and – despite being a piece of work – surprising potential if viewed from a certain angle. That said, I’m not even here to analyze her, I’m just here point out that people like that do exist, and many of them are worth saving.

I guess when it comes down to it, that’s why I love Tomoko so much: because she fucking needs it, and so does everyone like her.

Fucking beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This gave me so much more perspective. & I read it all in your voice. ❤ Thanks for not hanging yourself.

LikeLiked by 2 people